Program Notes Sonata No. 4 for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 23 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) German composer Ludwig van Beethoven casts such a long shadow as a composer that even nearly 200 years after his death he remains the subject of popular movies, scholarly. Beethoven originally intended this to be published as a contrasting companion piece to his 'Spring' Sonata, and indeed the two works appeared together as Op. In a new edition the following year, though, the violin parts of the two sonatas were mistakenly printed in different formats, and to save face and spare the costs of re-engraving, the sonatas were published 'as is' under. Program Notes Beethoven Chamber Series: Concert 4. And piano, violin sometimes substitutes for the clarinet: this version will be played today. Differences between the clarinet and optional violin part are few: descending lines in the clarinet are altered in the violin part when they would pass below its range, and some of the single notes. Musician's or Publisher's Notes. Beethoven originally intended this to be published as a contrasting companion piece to his 'Spring' Sonata, and indeed the two works appeared together as Op. However, due to a publishing error, the sonatas appeared in print under consecutive opus numbers, 'Spring' taking Op. Work is the so-called Devil’s Trill Sonata, said to have been inspired by a dream in which the Devil seized Tartini’s violin and began to play a tormented piece characterized by wild trilling. The Pastorale heard on this week’s program, which is an arrangement Respighi made in 1908 of Tartini’s Violin Sonata in A major, shows.

Beethoven, Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Major, Op. 12, No. 2

When Beethoven’s first set of three violin sonatas (Op. 12) went on sale at the end of 1798, the musical world of Vienna was no more ready for them than it had been for his other music. A review of the sonatas written in June 1799 makes such statements as:

After having looked through these strange sonatas, overladen with difficulties . . . [I] felt . . . exhausted and without having had any pleasure. . . . Bizarre . . . Learned, learned and always learned — and nothing natural, no song . . . a striving for strange modulations. . . .

Beethoven Violin Sonata 10

If Herr v. B. wished to deny himself a bit more and follow the course of nature he might, with his talent and industry, do a great deal for an instrument [the piano] which he seems to have so wonderfully under his control.

Such bad press obviously did not deter Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) from his vision. In all, he composed ten violin sonatas spread over his first and second style-periods, including the famous “Kreutzer” Sonata (Op. 47). The last violin sonata was composed in 1812 and published as Op. 96.

“Effervescence” is the word for the A Major Sonata’s first movement. Only momentarily does Beethoven depart from the tripping-skipping of the first and second themes. In the exposition, the only “serious” departure comes after those themes — a momentary catching of the breath before the composer whirls off in a new direction. In the brief development, Beethoven maximizes his small collection of ideas, and in the recapitulation, he extends them in a post-development that flies into a new key before a final landing in A major and a delightful coda.

“Dialogue” would be a good descriptor for the Andante. Interchanges of similar phrases between piano and violin characterize the lyrical outer sections. In the center, however, the two instruments become more closely entwined. Nineteenth-century writer Friederich Niecks commented that “the charm of the movement lies in its simplicity and naiveté and in the truth of its tender, plaintive accents.”

“Scherzo” might have been Beethoven’s appellation for the final movement, had he chosen that form. It has all the good-humored flavor of the best of Beethoven’s scherzos, and the composer himself used the word piacevole (pleasing) in the tempo marking. Following tradition, the movement is a rondo that presents the sunniest of themes, appropriately completing this “feel-good” sonata.

Beethoven, Violin Sonata No. 5 in F Major, Op. 24 (“Spring”)

It may be altogether too glib to say that Beethoven anticipated or pioneered every major musical development of the Romantic age that followed him. Yet, when listening to his aptly nicknamed “Spring” Sonata, the notion is tempting. Here, in a nutshell, Beethoven presents a pre-echo of the heartfelt spirit, naivety, and boldness of Mendelssohn and Schumann — as well as elements of their melodic and harmonic vocabulary.

The first movement is particularly illustrative. In its opening, we have the innocent freshness of a Mendelssohn, heard in melodious themes given first to the violin and then answered by the piano. A short development leads to the unprepared and surprising recapitulation. Now, the harmonic color of the principal themes is tinged with the pathos of experience, but the spirit of pure joy returns in the sumptuous coda.

The Adagio is more comparable to Schumann in its harmonic richness and full, pianistic textures. However, chamber music authority W.W. Cobbett maintains that the opening theme of this five-part form “seems to have escaped from some opera by Mozart.”

The very brief Scherzo movement turns again to a Mendelssohn-like spirit. Its elfin violin elody. However, it is accompanied by offset piano rhythms that could have come only from Beethoven’s pen.

Over the rondo finale, the big-hearted Schumannesque spirit hovers again, although there are occasional winks in the direction of Mozart. In contrast with the opening movement, the piano is usually the leader and the violin the follower in presenting new themes. One Beethovenian feature in the harmonic plan is a false recapitulation in the key of D major, which then slips deftly back into F major for the concluding sections.

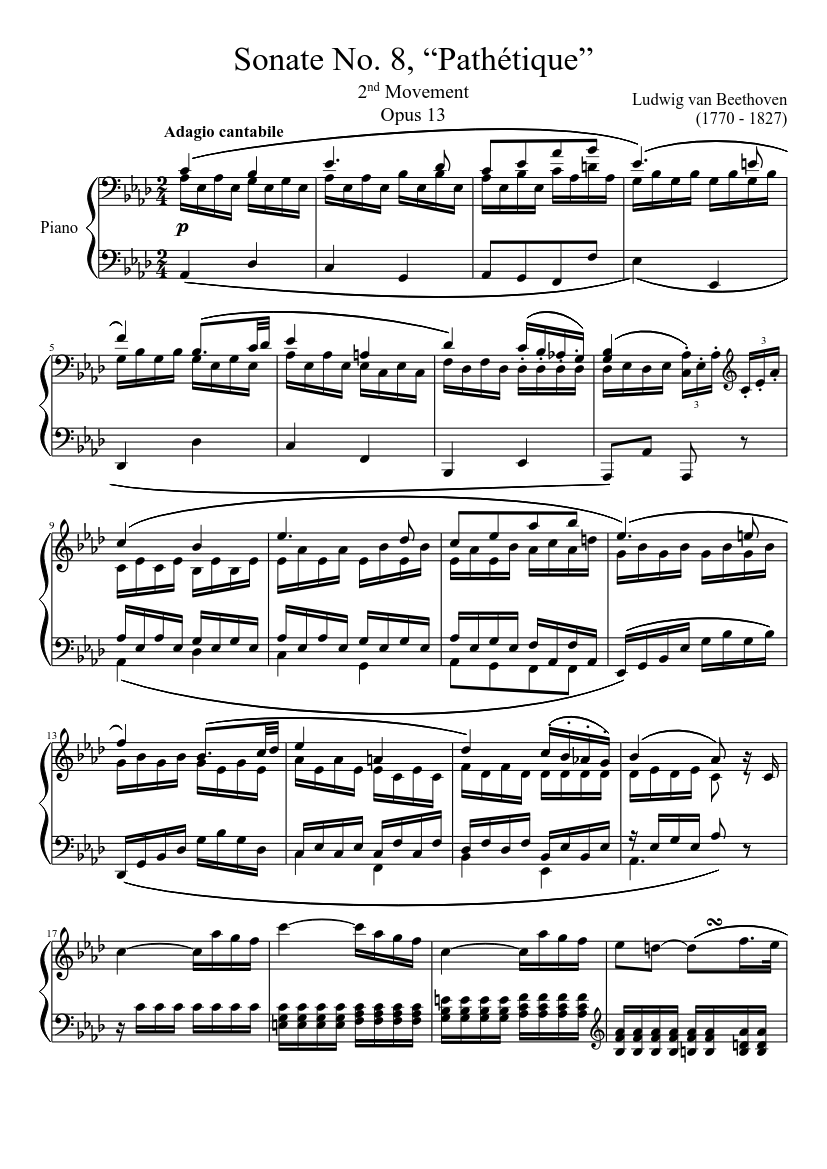

Beethoven composed the “Spring” Sonata in 1800 or 1801 and published it in the latter year alongside the Op. 23 Violin Sonata (no. 4). Much of the youth, vigor, and studied innocence of the “Spring” Sonata may be attributed to the early period in which the work was written. This was the time of Beethoven’s “Pathétique” Sonata for piano and the First Symphony, but a time before he fully realized (or admitted) his loss of hearing. Thus, with this sonata we might imagine Beethoven standing at the brink of the future. It is also easy to imagine this happening on a bright, sunlit day with a spring breeze wafting through the young master’s hair.

Beethoven, Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major, Op. 47 (“Kreutzer”)

Download Beethoven Violin Sonata 4 Program Notes Pdf

It seemed that entirely new impulses, new possibilities, were revealed to me in myself, such as I had not dreamed of before. Such works should be played only in grave, significant conditions, and only then when certain deeds corresponding to such music are to be accomplished.

These are not the words of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) nor of Kreutzer, but rather of Tolstoy’s tragic hero in the novella, The Kreutzer Sonata, where a performance of this sonata drives him over the edge of insanity, and he kills his wife. Fantastic as that notion seems, it is imaginable through the unrestraint of the first movement and the excitement of the last. However, none of that was Beethoven’s intention. He composed the “Kreutzer” Sonata in 1802-1803 just ahead of the “Eroica” Symphony. This was a turning point in Beethoven’s style, the entry into his “Heroic Decade,” to use Maynard Solomon’s expression.

This violin sonata was the longest written to date, just as the Third Symphony would be the longest of its genre yet heard. And, just as Beethoven changed the dedication of his symphony, he re-directed the dedication of the sonata. Originally, Beethoven wrote the work for George Bridgetower, with whom he premiered the music in 1803. However, the two subsequently fought over the attentions of a woman. Beethoven then used the sonata as a political tool for his proposed (but never accomplished) move to Paris by dedicating it to the French virtuoso, Rodolphe Kreutzer. Ironically, Kreutzer never performed the sonata, finding it, in the words of Berlioz, “outrageously unintelligible.”

Although that was an exaggeration, many violinists have found the first movement to be awkward. Another feature that may have put off Kreutzer is the equal prominence of the piano. In the sketches, Beethoven made the notation, “in a very concertante style, somewhat like a concerto.” But it is a concertante for both violin and piano: a concerto without orchestra.

Beethoven begins with the only slow introduction among the ten violin sonatas, and he periodically returns to Adagio in the course of the first movement. “Feverish,” “fiery,” and “passionate” are terms often applied to the Presto that follows. Beethoven seems to have created a contest for superiority between the two instruments, and only in the heat of the development section do they achieve true parity.

The theme and variations in the second movement are a complete contrast. Here, Beethoven reminds us that violin sonatas were originally salon or drawing-room music. The theme and first two variations follow that idea; however, the fourth (in the minor mode) is music of somber introspection. A final decorative variation and quiet coda round out the movement.

In his haste to complete this sonata for its premiere, Beethoven used for his last movement the discarded finale from the Violin Sonata, Op. 30, no. 1 (which it would have overbalanced). This galloping tarantella puts the sonata into a whirl that balances the first movement in length and emotional values. Slowing only occasionally, the motion of this music is relentless, driving breathlessly to a tempestuous finish

Dr. Michael Fink, copyright 2019

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61

THE VITAL STATS

COMPOSER: Born December 16, 1770, Bonn; died March 26, 1827, Vienna

WORK COMPOSED: 1806. Commissioned by and dedicated to Franz Clement, music director and concertmaster of the Theater an der Wien

WORLD PREMIERE: Clement performed the solo at the premiere, which Beethoven conducted at the Theater an der Wien on December 23, 1806.

INSTRUMENTATION: Solo violin, flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

ESTIMATED DURATION: 42 minutes

Ludwig van Beethoven’s only violin concerto is truly iconoclastic, and it shattered conventional notions of what an early Romantic concerto could be. Instead of using the concerto as a vehicle to show off the soloist’s technique, Beethoven recreated the genre, giving the soloist plenty of opportunities to display their talents with music full of depth and innovation.

Beethoven composed the Violin Concerto during a highly productive period that stretched from 1804 to 1806. During this time, Beethoven wrote some of his best-known music, including the Fourth Piano Concerto, the “Razumovsky” string quartets, the Fourth and Fifth symphonies, and the “Appassionata” Piano Sonata.

Franz Clement, the 21-year-old music director and concertmaster of the Theater an der Wien, commissioned the Violin Concerto. After the premiere, Clement made suggestions for revisions to the solo part, and Beethoven’s manuscript shows a number of corresponding alterations. Contrary to convention, Beethoven did not write a cadenza – the extended unaccompanied solo passage usually found at the end of the first movement – where the soloist demonstrates their technical and artistic skill. Presumably Clement improvised a cadenza at the premiere; since then, many violinists and composers have composed their own. Today’s audiences are probably most familiar with the cadenza created by violinist Fritz Kreisler.

Any piece of music can be spoiled by a poor performance. According to published accounts, Beethoven finished the concerto just two days before the premiere, which meant Clement had to sight-read the opening performance. Although it was beautiful – and staggeringly difficult to play – the lack of adequate rehearsal, among other factors, gave the Violin Concerto a bad reputation that took 30 years to overcome. In 1844, 12-year-old violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim played the concerto at his debut with the London Philharmonic. Joachim pored over the score, memorized the entire piece, and composed his own cadenzas in preparation. The hard work paid off, as one reviewer noted, “[Joachim] is perhaps the first violin player, not only of his age, but of his siècle [century]. He performed Beethoven’s solitary concerto, which we have heard all the great performers of the last twenty years attempt, and invariably fail in . . . its performance was an eloquent vindication of the master-spirit who imagined it.”

Unlike Beethoven’s concertos for piano, which feature thick, dense chords and difficult scalar passages, the violin solo is graceful and lyrical. This warm expressiveness matched Clement’s style of playing, which Beethoven said exemplified “an extremely delightful tenderness and purity.”

The concerto begins with five repeating notes in the timpani, an unconventional opening for any piece of music written in 1806. This simple knocking is repeated, like a gentle but persistent heartbeat, throughout the movement, and becomes a recurring motif. In another distinctive break from tradition, the soloist does not enter for a full three minutes, and then begins a cappella (alone), before reiterating the first theme in a high register.

The Larghetto’s main melody is stately, intimate, and tranquil, and becomes an orchestral backdrop over which the solo violin traces graceful arabesques in ethereally high registers. The soloist takes center stage in this movement, playing extended cadenzas and other passages with minimal accompaniment.

The final Rondo: Allegro flows seamlessly from the Larghetto; the soloist launches immediately into a rocking melody that suggests a boat bobbing at anchor. Typical rondo format features a primary theme (A), which is interspersed with contrasting sections (B, C, D, etc.). Each of these contrasting sections departs from the (A) theme, sometimes in mood, sometimes by shifting from major to minor, or by changing keys entirely.

MORTON GOULD

Stringmusic

THE VITAL STATS

COMPOSER: born December 10, 1913, New York, NY; died February 21, 1996, Orlando, FL

WORK COMPOSED: written for cellist, conductor, and music educator Mstislav Rostropovich and the National Symphony Orchestra, to commemorate Rostropovich’s retirement as conductor of the NSO

WORLD PREMIERE: Mstislav Rostropovich led the National Symphony Orchestra at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D. C., on March 10, 1994.

INSTRUMENTATION: string orchestra

ESTIMATED DURATION: 28 minutes

Composer, arranger, conductor, pianist, child prodigy: Morton Gould answered to all of these. His life and career traced the eclectic course of 20th-century American music, from vaudeville and Tin Pan Alley to Broadway and concert halls around the world. Gould made over 100 recordings, many of which became bestsellers, and a number of his compositions, including Stringmusic, are now part of the standard orchestral repertoire.

In January 1995, Gould told his biographer Peter Goodman, “I would love the Pulitzer Prize, which I will never get, by the way.” Three months later, Stringmusic won the prestigious composition award, much to Gould’s surprise and delight.

Stringmusic, which Gould composed for his friend and colleague Mstislav “Slava” Rostropovich, showcases all the possible sounds and colors of a string orchestra. In his program notes, Gould wrote, “Stringmusic is a large-scale suite, or serenade, for string orchestra . . . I have been especially concerned with contrasts in terms of color and texture; there is a great deal of antiphonal writing – sometimes to the extent of suggesting two separate string orchestras. Frequently I have one section playing entirely pizzicato (plucked strings) while the other plays arco (bowed). Basically, Stringmusic is a lyrical work, built entirely on original themes and reflecting, in a way, the many moods and many facets of a man and musician we have all come to know for the intensity and emotion of his commitment to music and life.”

“When Slava conducted my Latin American Symphonette in 1990 . . . he told me he especially liked the second movement, a Tango, because he is ‘a tango expert,’” Gould recalled. “ . . . After a somewhat strident Argentine-style tango episode, with its pronounced rhythm, there is a striking change to a languorous, voluptuous episode for four violins, in the old Mitteleuropa cafe style – a sort of parody, but not quite.”

The Dirge reflects “not only the intensity but in particular the sense of sorrow, loss, and even anger that must be associated with so much that Slava has experienced in consequence of his ideals and his loyalties,” said Gould. “The cortege-like quality of this elegiac music, I feel, is in keeping with a prominent part of his personality.” In the Ballad, which Gould describes as “a Lied for string orchestra, a sort of love note,” the emotional tension dissipates, and the concluding Strum “starts very fast, with tremolo effects and double notes and lots of contrast, and takes off as a real virtuoso piece, unreservedly jubilant.”

MILY BALAKIREV (ARR. CASELLA)

Islamey: Oriental Fantasy, Op. 18

Download Beethoven Violin Sonata 4 Program Notes Download

THE VITAL STATS

COMPOSER: born January 2, 1837, Nizhniy Novgorod; died St. Petersburg, May 29, 1910

WORK COMPOSED: Mily Balakirev began writing Islamey for solo piano on August 21, 1869, while visiting his friend and colleague Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and completed it on September 25 – “at 9:30 in the evening,” according to a note in the original manuscript – of that year in St. Petersburg. Balakirev published a revised version in 1902 and dedicated Islamey to pianist Nikolai Rubinstein.

WORLD PREMIERE: Rubinstein gave the premiere of the original piano version on December 12, 1869, in Moscow. Alfredo Casella created his orchestral arrangement between 1907 and 1908. Balakirev approved it, after making two revisions, and Casella premiered his orchestrated version in Paris in 1908. Casella dedicated his orchestration to Russian conductor Alexander Siloti.

MOST RECENT OREGON SYMPHONY PERFORMANCE: First performance

INSTRUMENTATION: Piccolo, 3 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, antique cymbals, bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, tambourine, tam tam, triangle, 2 harps, and strings

ESTIMATED DURATION: 9 minutes

One-upmanship sometimes plays a part in musical composition. In 1908, when Maurice Ravel began working on Gaspard de la nuit, considered the most technically challenging piano composition in the solo repertoire, he said he wanted to compose a piece “more difficult than Mily Balakirev’s Islamey.”

Balakirev wrote Islamey during a white-hot spate of inspiration in August and September 1869 for pianist Nikolai Rubenstein. Balakirev had traveled several times to the Caucasus region of Russia, where he heard the music that became the main theme of Islamey. In a letter to a friend, Balakirev shared his impressions of the area:

“ . . . the majestic beauty of luxuriant nature there and the beauty of the inhabitants that harmonises with it – all these things together made a deep impression on me . . . Since I interested myself in the vocal music there, I made the acquaintance of a Circassian prince, who frequently came to me and played folk tunes on his instrument, which was something like a violin. One of them, called Islamey, a dance-tune, pleased me extraordinarily and . . . I began to arrange it for the piano. The second theme was communicated to me in Moscow by an Armenian actor, who came from the Crimea and is, as he assured me, well known among the Crimean Tatars.”

Balakirev was an outstanding pianist in his own right, and much admired by his colleagues. Together with César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Alexander Borodin, Balakirev was known as one of the Mighty Five (Kucha), a group of Russian composers who established the Russian national sound. In his memoir My Musical Life, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote of Balakirev, “His personal fascination was enormous . . . He remembered every bar of music he had ever heard, memorized instantly all compositions played to him.”

Not long before Balakirev died, Italian conductor and composer Alfredo Casella arranged Islamey for orchestra. In this version, Casella, also a virtuoso pianist, preserves Islamey’s breakneck speed and high spirits, and his deft orchestration emphasizes Balakirev’s brilliant colors and dazzling effects.

© 2017 Elizabeth Schwartz

Elizabeth Schwartz is a free-lance writer, musician, and music historian based in Portland. In addition to annotating programs for the Oregon Symphony, the Oregon Bach Festival, Chamber Music Northwest, and other organizations, she has contributed to the nationally syndicated radio program “Performance Today,” produced by American Public Media. Schwartz also writes about performing arts and culture for Oregon Jewish Life Magazine. www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com

RECOMMENDED RECORDINGS

Beethoven Violin And Piano Sonatas

Beethoven-Violin Concerto

Itzhak Perlman-Violin

Carlo Maria Giulini-Philharmonia Orchestra

EMI/Warner Classics 552362

Wolfgang Schneiderhan-Violin

Eugen Jochum-Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Deutsche Grammophon Originals 447403

Morton Gould-Stringmusic

David Alan Miller-Albany Symphony Orchestra

Albany 300

Beethoven Violin Sonata No 7

Balakirev/Casella-Islamey

Beethoven Violin Sonata 4

Eugene Goosens-Philharmonia Orchestra

Medici Classics 9-2 (Casella arr.)

Download Beethoven Violin Sonata 4 Program Notes Free

Valery Gergiev-Kirov Orchestra

Philips 470840 (Lyapunov arr.)